An acorn falls to the ground and eventually sprouts tiny, frail stems that reach toward the warm sunlight. It sends roots into the ground to anchor itself and, growing just a little bit each day, becomes a seedling and then a small tree. The wind blows, the droughts come, the seasons change, and through it all the young tree perseveres. In time, it becomes a tall, sturdy, beautiful oak, producing more acorns which eventually add up to an entire forest.

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Forms Library

Basic Charts & Worksheets

Every family genealogist needs certain basic charts and worksheets for tracking ancestors and research progress. The forms listed on this link belong in every genealogist's basic toolkit: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/basicforms

Oral History Interview Record

Family history isn't just about records and vital statistics ... it's also about the stories, memories and traditions you want to pass on to future generations. The forms listed on this link will help you preserve those precious pieces of your family's past: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/oralhistoryforms

Census Worksheets

Use the forms listed on this link to record information found in U.S. censuses: www.familytreemagazine.com/censusforms

Immigration Forms

The forms listed on this link are for transcribing names and information about immigrants you find on customs lists (the name for early passenger lists) and ship manifests (more-modern passenger lists). Due to changing immigration laws, shipping companies had to record different information about passengers through the years: www.familytreemagazine.com/immigrationforms

Record Worksheets

As you study genealogical records, the worksheets listed on this link help to keep detailed records of your findings: By transcribing and abstracting information, you make sure you don't miss any tidbits that may be helpful to you later: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/recordworksheets

Research Trackers & Organizers

The forms listed on this link will help you to keep tabs on your genealogy plans and progress, so you can research more efficiently. Great for tracking which records you've searched, which ones you need to search and what's still in the works: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/researchforms

These forms and more found at http://www.familytreemagazine.com/.

Every family genealogist needs certain basic charts and worksheets for tracking ancestors and research progress. The forms listed on this link belong in every genealogist's basic toolkit: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/basicforms

Oral History Interview Record

Family history isn't just about records and vital statistics ... it's also about the stories, memories and traditions you want to pass on to future generations. The forms listed on this link will help you preserve those precious pieces of your family's past: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/oralhistoryforms

Census Worksheets

Use the forms listed on this link to record information found in U.S. censuses: www.familytreemagazine.com/censusforms

Immigration Forms

The forms listed on this link are for transcribing names and information about immigrants you find on customs lists (the name for early passenger lists) and ship manifests (more-modern passenger lists). Due to changing immigration laws, shipping companies had to record different information about passengers through the years: www.familytreemagazine.com/immigrationforms

Record Worksheets

As you study genealogical records, the worksheets listed on this link help to keep detailed records of your findings: By transcribing and abstracting information, you make sure you don't miss any tidbits that may be helpful to you later: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/recordworksheets

Research Trackers & Organizers

The forms listed on this link will help you to keep tabs on your genealogy plans and progress, so you can research more efficiently. Great for tracking which records you've searched, which ones you need to search and what's still in the works: http://www.familytreemagazine.com/info/researchforms

These forms and more found at http://www.familytreemagazine.com/.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Ten Commandments of Genealogy

The following article is from Eastman's Online Genealogy Newsletter and is copyright by Richard W. Eastman. It is re-published here with the permission of the author. Information about the newsletter is available at http://www.eogn.com.

In the course of writing this newsletter, I get to see a lot of genealogy information. Most of what I see is on the Web, although some information is in books or in e-mail. Some of what I see is high-quality research. However, much of it is much less than that. Even the shoddiest genealogy work could be so much more if the compiler had simply spent a bit of time thinking about what he or she was doing.

Creating a first-class genealogy work is not difficult. In fact, it is expected. It should be the norm. Please consider the following "rules." If you follow these guidelines, you, too, can produce high-quality genealogy reports that will be useful to others:

Footnote #1: A primary record is one created at or immediately after the occurrence of the event cited. The record was created by someone who had person knowledge of the event. Examples include marriage records created by the minister, census records, death certificates created within days after the death, etc. Nineteenth century and earlier source records will be in the handwriting of the person who recorded the event, such as the minister, town clerk or census taker.

Footnote #2: A secondary record is one made years after the original event, usually by someone who was not at the original event and did not have personal knowledge of the participants. Most published genealogy books are secondary sources; the authors are writing about events that occurred many years before they wrote about the event. Transcribed records are always secondary sources and may have additional errors created inadvertently by the transcriber(s). Most online databases are transcribed (secondary) sources.

In the course of writing this newsletter, I get to see a lot of genealogy information. Most of what I see is on the Web, although some information is in books or in e-mail. Some of what I see is high-quality research. However, much of it is much less than that. Even the shoddiest genealogy work could be so much more if the compiler had simply spent a bit of time thinking about what he or she was doing.

Creating a first-class genealogy work is not difficult. In fact, it is expected. It should be the norm. Please consider the following "rules." If you follow these guidelines, you, too, can produce high-quality genealogy reports that will be useful to others:

- Never accept someone else's opinion as "fact." Be suspicious. Always check for yourself!

- Always verify primary sources (see Footnote #1); never accept a secondary source (see Footnote #2) as factual until you have personally verified the information.

- Cite your sources! Every time you refer to a person's name, date and/or place of an event, always tell where you found the information. If you are not certain how to do this, get yourself a copy of "Evidence Explained" by Elizabeth Shown Mills. This excellent book shows both the correct form of source citation and the sound analysis of evidence.

- If you use the works of others, always give credit. Never claim someone else's research as your own.

- Assumptions and "educated guesses" are acceptable in genealogy as long as they are clearly labeled as such. Never offer your theories as facts.

- Be open to corrections. The greatest genealogy experts of all time make occasional errors. So will you. Accept this as fact. When someone points out a possible error in your work, always thank that person for his or her assistance and then seek to re-verify your original statement(s). Again, check primary sources.

- Respect the privacy of living individuals. Never reveal personal details about living individuals without their permission. Do not reveal their names or any dates or locations.

- Keep "family secrets." Not everyone wants the information about a court record or a birth out of wedlock to be posted on the Internet or written in books. The family historian records "family secrets" as facts but does not publish them publicly.

- Protect original documents. Handle all documents with care, and always return them to their rightful storage locations.

- Be prepared to reimburse others for reasonable expenses incurred on your behalf. If someone travels to a records repository and makes photocopies for you, always offer to reimburse the expenses.

Footnote #1: A primary record is one created at or immediately after the occurrence of the event cited. The record was created by someone who had person knowledge of the event. Examples include marriage records created by the minister, census records, death certificates created within days after the death, etc. Nineteenth century and earlier source records will be in the handwriting of the person who recorded the event, such as the minister, town clerk or census taker.

Footnote #2: A secondary record is one made years after the original event, usually by someone who was not at the original event and did not have personal knowledge of the participants. Most published genealogy books are secondary sources; the authors are writing about events that occurred many years before they wrote about the event. Transcribed records are always secondary sources and may have additional errors created inadvertently by the transcriber(s). Most online databases are transcribed (secondary) sources.

Monday, December 27, 2010

"Give me your tired, your poor ..."

Standing in New York Harbor at the very portal of the New World, the Statue of Liberty, one of the most colossal sculptures in the history of the world, has greeted many millions of the oppressed and venturesome of other lands who crossed the ocean in hopeful search of greater freedom and opportunity. To them, and to the whole world, the statue has become the symbol of those ideals of human liberty upon which our Nation and its form of government were founded.

Standing in New York Harbor at the very portal of the New World, the Statue of Liberty, one of the most colossal sculptures in the history of the world, has greeted many millions of the oppressed and venturesome of other lands who crossed the ocean in hopeful search of greater freedom and opportunity. To them, and to the whole world, the statue has become the symbol of those ideals of human liberty upon which our Nation and its form of government were founded.To the poet Emma Lazarus, who saw refugees from persecution arriving on a tramp steamer, following incredible sufferings, the statue was The New Colossus or the Mother of Exiles. She wrote of it in 1883:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

In its international aspect the statue, which was a gift from the people of France to the people of the United States, commemorates the long friendship between the peoples of the two Nations ... a friendship that has continued since the American Revolution when, implemented by the French with sinews of war, it helped turn the tide of victory to the side of the Colonies.

ELLIS ISLAND HISTORY

from EllisIsland.org

Ellis Island, a small island in New York Harbor, is located in the upper bay just off the New Jersey coast, within the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. From 1892 to 1954, over twelve million immigrants entered the United States through this gateway to the new world.

Before being designated as the site of the first Federal immigration station by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890, Ellis Island had a varied history. The local Indian tribes had called it "Kioshk" or Gull Island. Due to its rich and abundant oyster beds and plentiful and profitable shad runs, it was known as Oyster Island for many generations during the Dutch and English colonial periods. By the time Samuel Ellis became the island's private owner in the 1770s, the island had been called Kioshk, Oyster, Dyre, Bucking and Anderson's Island. In this way, Ellis Island developed from a sandy island that barely rose above the high tide mark, into a hanging site for pirates, a harbor fort, ammunition and ordinance depot named Fort Gibson and finally into an immigration station.

From 1794 to 1890, Ellis Island played a mostly uneventful but still important military role in United States history. When the British occupied New York City during the duration of the Revolutionary War, its large and powerful naval fleet was able to sail unimpeded directly into New York Harbor. Therefore, it was deemed critical by the United States Government that a series of coastal fortifications in New York Harbor be constructed just prior to the War of 1812. After much legal haggling over ownership of the island, the Federal government purchased Ellis Island from New York State in 1808. Ellis Island was approved as a site for fortifications and on it was constructed a parapet for three tiers of circular guns, making the island part of the new harbor defense system that included Castle Clinton at the Battery, Castle Williams on Governor's Island, Fort Wood on Bedloe's Island and two earthworks forts at the entrance to New York Harbor at the Verrazano Narrows. The fort at Ellis Island was named Fort Gibson in honor of a brave officer killed during the War of 1812.

Prior to 1890, the individual states (rather than the Federal government) regulated immigration into the United States. Castle Garden in the Battery (originally known as Castle Clinton) served as the New York State immigration station from 1855 to 1890 and approximately eight million immigrants, mostly from Northern and Western Europe, passed through its doors. These early immigrants came from nations such as England, Ireland, Germany and the Scandinavian countries and constituted the first large wave of immigrants that settled and populated the United States. Throughout the 1800s and intensifying in the latter half of the 19th century, ensuing political instability, restrictive religious laws and deteriorating economic conditions in Europe began to fuel the largest mass human migration in the history of the world. It soon became apparent that Castle Garden was ill-equipped and unprepared to handle the growing numbers of immigrants arriving yearly. Unfortunately compounding the problems of the small facility were the corruption and incompetence found to be commonplace at Castle Garden.

The Federal government intervened and constructed a new Federally-operated immigration station on Ellis Island. While the new immigration station on Ellis Island was under construction, the Barge Office at the Battery was used for the processing of immigrants. The new structure on Ellis Island, built of "Georgia pine" opened on January 1, 1892; Annie Moore, a 15 year-old Irish girl, accompanied by her two brothers entered history and a new country as she was the very first immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island on January 2. Over the next 62 years, more than 12 million were to follow through this port of entry.

While there were many reasons to emigrate to America, no reason could be found for what would occur only five years after the Ellis Island Immigration Station opened. During the evening of June 14, 1897, a fire on Ellis Island, burned the immigration station completely to the ground. Although no lives were lost, many years of Federal and State immigration records dating back to 1855 burned along with the pine buildings that failed to protect them. The United States Treasury quickly ordered the immigration facility be replaced under one very important condition. All future structures built on Ellis Island had to be fireproof. On December 17, 1900, the new Main Building was opened and 2,251 immigrants were received that day.

While most immigrants entered the United States through New York Harbor (the most popular destination of steamship companies), others sailed into many ports such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco and Savannah, Miami, and New Orleans. The great steamship companies like White Star, Red Star, Cunard and Hamburg-America played a significant role in the history of Ellis Island and immigration in general. First and second class passengers who arrived in New York Harbor were not required to undergo the inspection process at Ellis Island. Instead, these passengers underwent a cursory inspection aboard ship; the theory being that if a person could afford to purchase a first or second class ticket, they were less likely to become a public charge in America due to medical or legal reasons. The Federal government felt that these more affluent passengers would not end up in institutions, hospitals or become a burden to the state. However, first and second class passengers were sent to Ellis Island for further inspection if they were sick or had legal problems.

This scenario was far different for "steerage" or third class passengers. These immigrants traveled in crowded and often unsanitary conditions near the bottom of steamships with few amenities, often spending up to two weeks seasick in their bunks during rough Atlantic Ocean crossings. Upon arrival in New York City, ships would dock at the Hudson or East River piers. First and second class passengers would disembark, pass through Customs at the piers and were free to enter the United States. The steerage and third class passengers were transported from the pier by ferry or barge to Ellis Island where everyone would undergo a medical and legal inspection.

If the immigrant's papers were in order and they were in reasonably good health, the Ellis Island inspection process would last approximately three to five hours. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), where doctors would briefly scan every immigrant for obvious physical ailments. Doctors at Ellis Island soon became very adept at conducting these "six second physicals." By 1916, it was said that a doctor could identify numerous medical conditions (ranging from anemia to goiters to varicose veins) just by glancing at an immigrant. The ship's manifest log (that had been filled out back at the port of embarkation) contained the immigrant's name and his/her answers to twenty-nine questions. This document was used by the legal inspectors at Ellis Island to cross examine the immigrant during the legal (or primary) inspection. The two agencies responsible for processing immigrants at Ellis Island were the United States Public Health Service and the Bureau of Immigration (later known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service - INS). On March 1, 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service was re-structured and included into 3 separate bureaus as part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

If the immigrant's papers were in order and they were in reasonably good health, the Ellis Island inspection process would last approximately three to five hours. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), where doctors would briefly scan every immigrant for obvious physical ailments. Doctors at Ellis Island soon became very adept at conducting these "six second physicals." By 1916, it was said that a doctor could identify numerous medical conditions (ranging from anemia to goiters to varicose veins) just by glancing at an immigrant. The ship's manifest log (that had been filled out back at the port of embarkation) contained the immigrant's name and his/her answers to twenty-nine questions. This document was used by the legal inspectors at Ellis Island to cross examine the immigrant during the legal (or primary) inspection. The two agencies responsible for processing immigrants at Ellis Island were the United States Public Health Service and the Bureau of Immigration (later known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service - INS). On March 1, 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service was re-structured and included into 3 separate bureaus as part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Despite the island's reputation as an "Island of Tears", the vast majority of immigrants were treated courteously and respectfully, and were free to begin their new lives in America after only a few short hours on Ellis Island. Only two percent of the arriving immigrants were excluded from entry. The two main reasons why an immigrant would be excluded were if a doctor diagnosed that the immigrant had a contagious disease that would endanger the public health or if a legal inspector thought the immigrant was likely to become a public charge or an illegal contract laborer.

During the early 1900s, immigration officials mistakenly thought that the peak wave of immigration had already passed. Actually, immigration was on the rise and in 1907, more people immigrated to the United States than any other year; approximately 1.25 million immigrants were processed at Ellis Island in that one year. Consequently, masons and carpenters were constantly struggling to enlarge and build new facilities to accommodate this greater than anticipated influx of new immigrants. Hospital buildings, dormitories, contagious disease wards and kitchens were all were feverishly constructed between 1900 and 1915.

As the United States entered World War I, immigration to the United States decreased. Numerous suspected enemy aliens throughout the United States were brought to Ellis Island under custody. Between 1918 and 1919, detained suspected enemy aliens were transferred from Ellis Island to other locations in order for the United States Navy with the Army Medical Department to take over the island complex for the duration of the war. During this time, regular inspection of arriving immigrants was conducted on board ship or at the docks. At the end of World War I, a big "Red Scare" spread across America and thousands of suspected alien radicals were interned at Ellis Island. Hundreds were later deported based upon the principal of guilt by association with any organizations advocating revolution against the Federal government. In 1920, Ellis Island reopened as an immigration receiving station and 225,206 immigrants were processed that year.

From the very beginning of the mass migration that spanned the years (roughly) 1880 to 1924, an increasingly vociferous group of politicians and nativists demanded increased restrictions on immigration. Laws and regulations such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Alien Contract Labor Law and the institution of a literacy test barely stemmed this flood tide of new immigrants. Actually, the death knell for Ellis Island, as a major entry point for new immigrants, began to toll in 1921. It reached a crescendo between 1921 with the passage of the Quota Laws and 1924 with the passage of the National Origins Act. These restrictions were based upon a percentage system according to the number of ethnic groups already living in the United States as per the 1890 and 1910 Census. It was an attempt to preserve the ethnic flavor of the "old immigrants", those earlier settlers primarily from Northern and Western Europe. The perception existed that the newly arriving immigrants mostly from southern and eastern Europe were somehow inferior to those who arrived earlier.

After World War I, the United States began to emerge as a potential world power. United States embassies were established in countries all over the world, and prospective immigrants now applied for their visas at American consulates in their countries of origin. The necessary paperwork was completed at the consulate and a medical inspection was also conducted there. After 1924, the only people who were detained at Ellis Island were those who had problems with their paperwork, as well as war refugees and displaced persons.

Ellis Island still remained open for many years and served a multitude of purposes. During World War II, enemy merchant seamen were detained in the baggage and dormitory building. The United States Coast Guard also trained about 60,000 servicemen there. In November of 1954 the last detainee, a Norwegian merchant seaman named Arne Peterssen was released, and Ellis Island officially closed.

GREAT LINKS

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hh/11/hh11a.htm

Large collection of historical documents from the 1800s through 1954 with concentrations in Steamship and Ocean Liner documents and photographs, Passenger Lists, U.S. Navy Archives and addtional materials covering World Wars I and II, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Immigration documents from Ellis Island, Castle Garden and other Immigration Stations: http://www.gjenvick.com/#ixzz10NebdVNOhttp://www.gjenvick.com/

Selected Images of Ellis Island and Immigration, ca. 1880-1920: http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/list/070_immi.html

Sunday, December 26, 2010

Saturday, December 25, 2010

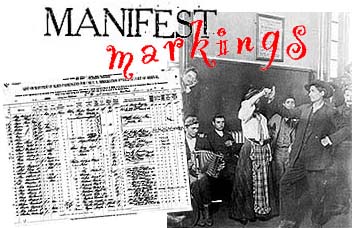

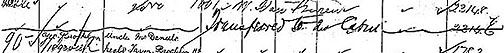

A Guide to Interpreting Passenger List Annotations

with the assistance of Elise Friedman, Flora Gursky & Eleanor Bien

Passenger Lists or manifests. Every genealogist and his sister wants to find one. But after years of searching, many find a document that raises as many questions as it answers. This is especially true of passenger lists dating after 1892, which are frequently found to have a variety of markings, codes, and annotations squeezed into the margins and small blank spaces above and behind information written in the list form's columns.

These web pages are intended to provide a comprehensive reference guide to interpreting the markings, or annotations, found on immigration passenger lists. It is written for researchers with a U.S. passenger list in hand. To learn more about finding passenger lists, see JewishGen's Immigration InfoFiles and the Passenger Lists section of the JewishGen FAQ. The information is generally organized by where the annotation is found on the record--in the left margin, for example, or in the occupation column. Within each location category are examples of the various types of annotations found in that space, and an explanation of each. Every attempt has been made to provide several examples of each annotation type so that researchers may come to recognize the form and pattern that characterizes each type. Each page also has a link to a glossary of commonly-found acronyms and abbreviations.

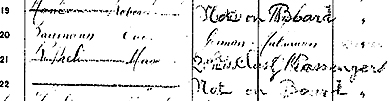

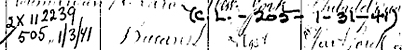

MARKINGS ON THE MANIFEST’S LEFT MARGIN

Nearly every manifest annotation found in the far left margin was made either prior to or upon arrival, usually during immigrant inspection. Steamship company clerks found the small margin of empty paper space useful for noting a variety of information. Immigrant Inspectors also used the empty space to leave clues as to whether an immigrant passed through inspection easily, or faced closer scrutiny.

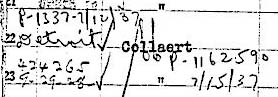

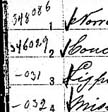

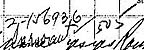

Numbers like those above are occasionally found in the left margin, especially on lists of ships from England. The numbers can have as few as 2 or 3 digits, and as many as 6 or 7 digits. These are "contract ticket" numbers issued by the steamship companies when contracting with the immigrant for their passage. The number may or may not have appeared on the immigrant's actual ticket or receipt. The steamship lines used the number as a personal identifier, and recording the number allowed the companies to match the manifest record with other business records. The numbers bear no relation to any other United States records. However, they may be useful in matching a U.S. passenger arrival record with a British departure record (British "outbound lists").

Numbers like those above are occasionally found in the left margin, especially on lists of ships from England. The numbers can have as few as 2 or 3 digits, and as many as 6 or 7 digits. These are "contract ticket" numbers issued by the steamship companies when contracting with the immigrant for their passage. The number may or may not have appeared on the immigrant's actual ticket or receipt. The steamship lines used the number as a personal identifier, and recording the number allowed the companies to match the manifest record with other business records. The numbers bear no relation to any other United States records. However, they may be useful in matching a U.S. passenger arrival record with a British departure record (British "outbound lists"). Lists from the 1890's or even the very early 1900's may have been printed by the steamship line with a "Contract Ticket" number column. This has been seen on passenger lists of the American Line from England in the mid-1890's. The presence of such a column demonstrates the importance of the information to the steamship company, and helps explain why it might be annotated at left on a list without a "Contract Ticket" column.

In some rare cases, typically on earlier lists prior to addition of the "Head Tax" column, a solitary number will appear to the left of a passenger's name. These lonely numbers are usually Head Tax receipt numbers. Notation of the receipt number may indicate either that the immigrant requested a receipt, disputed his/her requirement to pay the tax, or was only passing through the U.S. in transit (in which case the Head Tax deposit would be refunded upon their departure).

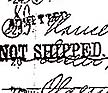

Not Shipped, N.O.B. or Did Not Sail

Often passengers booked to sail on a given ship did not depart. Perhaps they missed the ship, or changed their travel plans, or became ill and health officials prevented them from boarding the ship. Whatever the case, in some instances the change or decision occurred so late there was no time to amend the passenger list. Their names and passenger information remain on lists for ships upon which they never arrived.

Often passengers booked to sail on a given ship did not depart. Perhaps they missed the ship, or changed their travel plans, or became ill and health officials prevented them from boarding the ship. Whatever the case, in some instances the change or decision occurred so late there was no time to amend the passenger list. Their names and passenger information remain on lists for ships upon which they never arrived.Some records remain without a line, but are noted in the left margin as "N.O.B." (Not On Board), "did not sail," or, like the stamp above, "Not Shipped." It was important for the steamship company to make clear who was and was not on board the ship when it arrived in the United States. The company was responsible for paying the Head Tax on each immigrant landed, and government officials calculated the company's monthly bill using the manifest lists. The passenger booked below "cancelled."

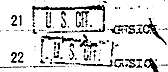

Note well that some of those names "lined out" were on board, but are officially recorded on another page of the passenger list. The example below includes two crossed-off names because they were "Not on Board," but one name is lined-out (line 21) because he/she is a "2nd class passenger." The official record of that person is, then, on the list of second class passengers.

Extremely common are letters and stamps in the left margin relating to an immigrant's detention or their being held for a Board of Special Inquiry hearing. The general rule is that some notation was made at left to indicate the immigrant was held for some reason. One cannot determine the reason by looking at the annotation, and unless it was subsequently stamped "Admitted" or "Deported," one cannot determine the outcome.

Extremely common are letters and stamps in the left margin relating to an immigrant's detention or their being held for a Board of Special Inquiry hearing. The general rule is that some notation was made at left to indicate the immigrant was held for some reason. One cannot determine the reason by looking at the annotation, and unless it was subsequently stamped "Admitted" or "Deported," one cannot determine the outcome. Unfortunately, for many passenger lists there is no additional information on the immigrant's fate. To date, additional records are known to survive for only two ports, and only for certain years. These ports are New York and Philadelphia.

Unfortunately, for many passenger lists there is no additional information on the immigrant's fate. To date, additional records are known to survive for only two ports, and only for certain years. These ports are New York and Philadelphia. Philadelphia records of detained immigrants (including those held for hearings) are extensive. They date from 1882 but only extend to ca. 1909. Some, dating from 1893 to 1909, are on microfilm as National Archives publication M1500. The majority remain in hard copy at the Regional Archives in Philadelphia. Anyone finding a detention annotation on a Philadelphia passenger list from this era should seriously consider investigating the Philadelphia detention records. And for Jewish immigrants, they might also consider the HIAS records in the Jewish Archives at Philadelphia's Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies.

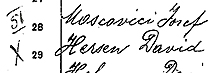

MARKINGS IN THE MANIFEST’S NAME COLUMN

One would assume any annotations in the name column would concern the immigrants' names, and many do. In some cases the name might have been clarified or corrected by a steamship company employee or an Immigrant Inspector.

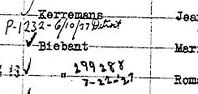

One would assume any annotations in the name column would concern the immigrants' names, and many do. In some cases the name might have been clarified or corrected by a steamship company employee or an Immigrant Inspector.Letters "V/L" Followed by Numbers Over Numbers, Sometimes With a Date

Prior to 1924, there were no "Reentry Permits." This meant that immigrants living in the United States, who wanted to travel abroad, had no assurance they would be readmitted to the U.S. upon return. Many of them would contact the Immigration Service prior to travel and ask for some paper, or pass, to guarantee their reentry. A practice developed, especially at Ellis Island, to issue such immigrants a letter from the Port Commissioner documenting the immigrant's previous admission for permanent residence. The letter was not a guarantee, but greatly facilitated the immigrant's travel.

Prior to 1924, there were no "Reentry Permits." This meant that immigrants living in the United States, who wanted to travel abroad, had no assurance they would be readmitted to the U.S. upon return. Many of them would contact the Immigration Service prior to travel and ask for some paper, or pass, to guarantee their reentry. A practice developed, especially at Ellis Island, to issue such immigrants a letter from the Port Commissioner documenting the immigrant's previous admission for permanent residence. The letter was not a guarantee, but greatly facilitated the immigrant's travel.When the clerk verified (checked) the original passenger list in these cases, he or she would annotate the list to show the activity. The letters "V/L" or "V L" stand for Verification of Landing. The numbers refer to a New York (usually) file number wherein records of all these transactions were filed. The file did not relate to the individual. Rather, it contained stacks of incoming and outgoing letters on verification of landing matters. The files no longer survive. The annotations can be helpful, though, in that they suggest the immigrant was planning a trip abroad and may appear again on a later passenger list.

It may be that some of these verifications were performed for reasons other than reentry letters. For example, any other instance where an immigrant requested proof that he or she had been legally admitted to the United States. And there are occasions when one will find the "V/L" annotation format dated later than 1924. To see common references to Reentry Permits after July 1924, see below, and see the page on Visa annotations.

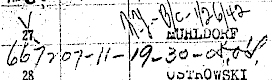

Letter "P" Or Word "Permit" With Numbers

After July 1, 1924, immigrants in the United States who wished to travel abroad could apply for and obtain a Reentry Permit. The process involved filing an application, submitting a fee, and waiting for the permit to arrive prior to departure. The application required the immigrant to name their original port, date, and ship of arrival so the record could be checked and verified. During the verification, a clerk would annotate the original record with the letter "P" or the entire word "permit," followed by the application number. The annotations can be helpful in that they suggest the immigrant was planning a trip abroad and may appear again on a later passenger list. To see the Reentry Permit noted on the return trip passenger list, see the page

After July 1, 1924, immigrants in the United States who wished to travel abroad could apply for and obtain a Reentry Permit. The process involved filing an application, submitting a fee, and waiting for the permit to arrive prior to departure. The application required the immigrant to name their original port, date, and ship of arrival so the record could be checked and verified. During the verification, a clerk would annotate the original record with the letter "P" or the entire word "permit," followed by the application number. The annotations can be helpful in that they suggest the immigrant was planning a trip abroad and may appear again on a later passenger list. To see the Reentry Permit noted on the return trip passenger list, see the page on Visa annotations.

Both examples above and below show annotations including the word "Detroit," indicating the applications were filed in Detroit, Michigan, the INS office serving immigrant's current residence.

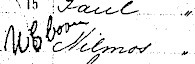

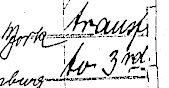

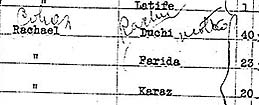

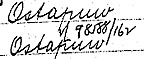

Clarified Or Corrected Names

The if, when, and how of immigrant name-changing on ship passenger lists is a matter of unending controversy. But there were simple rules. Many names were clarified as in the two examples shown here. This clarification may have been performed by a steamship company clerk prior to departure, by the ship's purser during the voyage, or by an Immigrant Inspector during the inspection process. Note the alternate names or spellings are written above or beside the original name, in a manner that would no doubt confound anyone wanting to transcribe the list.

The if, when, and how of immigrant name-changing on ship passenger lists is a matter of unending controversy. But there were simple rules. Many names were clarified as in the two examples shown here. This clarification may have been performed by a steamship company clerk prior to departure, by the ship's purser during the voyage, or by an Immigrant Inspector during the inspection process. Note the alternate names or spellings are written above or beside the original name, in a manner that would no doubt confound anyone wanting to transcribe the list. In other instances one will find a name deliberately crossed out (just the name, not across the entire page) and another name or alternate spelling entered. In these cases the name has been officially corrected according to standard bureaucratic procedure. Immigrants who arrived after June 29, 1906, often later encountered problems naturalizing because their immigration record name did not match their true name, and their immigration record name had to appear on the Petition for Naturalization. They could, if they desired, apply for a correction of the passenger list record. In addition to filing a form (of course), they submitted evidence that they and the immigrant on the passenger list were in fact one and the same person. When the request was approved, a government clerk was authorized to officially correct the record. He/she would cross out the old name and write in the new. In rare cases one will also find dates or file number references included in this annotation.

In other instances one will find a name deliberately crossed out (just the name, not across the entire page) and another name or alternate spelling entered. In these cases the name has been officially corrected according to standard bureaucratic procedure. Immigrants who arrived after June 29, 1906, often later encountered problems naturalizing because their immigration record name did not match their true name, and their immigration record name had to appear on the Petition for Naturalization. They could, if they desired, apply for a correction of the passenger list record. In addition to filing a form (of course), they submitted evidence that they and the immigrant on the passenger list were in fact one and the same person. When the request was approved, a government clerk was authorized to officially correct the record. He/she would cross out the old name and write in the new. In rare cases one will also find dates or file number references included in this annotation. Correspondence Or Record Checks With Other Agencies Or Governments

Among the most perplexing annotations are references to various record checks and correspondence lacking enough information for modern researchers to decipher their meaning. That said, familiarity with immigration records and procedure can often provide likely explanations or possibilities for further research. The example above includes an Ellis Island correspondence file number, "98588/162." Ellis Island files generally begin with "98" or "99." What was the subject of the correspondence? We may never know.

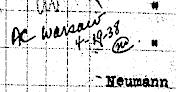

Among the most perplexing annotations are references to various record checks and correspondence lacking enough information for modern researchers to decipher their meaning. That said, familiarity with immigration records and procedure can often provide likely explanations or possibilities for further research. The example above includes an Ellis Island correspondence file number, "98588/162." Ellis Island files generally begin with "98" or "99." What was the subject of the correspondence? We may never know. Another example reads "AC Warsaw 4-19-38" with what looks like the initial of whoever verified the record. "AC Warsaw" is almost certainly a reference to the United States (American) Consul in Warsaw, Poland. The U.S. Foreign Service, though the Department of State, often requested record checks from the Immigration Service in the cases of Americans in distress abroad, of immigrants stranded abroad while on a visit to the Old Country, or in connection with visa applications beginning in the early 1920's. The annotation at right indicates that in 1938 the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw had some interest in the immigrant listed. It could be the immigrant was in Warsaw, or perhaps one of the immigrant's relatives applied for a visa in Warsaw, and named the immigrant as his sponsor.

Another example reads "AC Warsaw 4-19-38" with what looks like the initial of whoever verified the record. "AC Warsaw" is almost certainly a reference to the United States (American) Consul in Warsaw, Poland. The U.S. Foreign Service, though the Department of State, often requested record checks from the Immigration Service in the cases of Americans in distress abroad, of immigrants stranded abroad while on a visit to the Old Country, or in connection with visa applications beginning in the early 1920's. The annotation at right indicates that in 1938 the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw had some interest in the immigrant listed. It could be the immigrant was in Warsaw, or perhaps one of the immigrant's relatives applied for a visa in Warsaw, and named the immigrant as his sponsor.This annotation is also believed to relate to a passport or visa application to the Department of State. We know that by 1930 the State Department was active processing visa applications for relatives, and issuing passports to naturalized U.S. citizens. The annotation seems to list an application number, then a date (November 19, 1930), then the reference "D.O.S." On the other hand, the numbers may NOT relate to an application or a date, and the initials may be those of the verifier. We often must make our best guess based on understanding of immigration procedure of the time. In the same vein, the annotation on the line above our example seems to refer to correspondence between the New York (NY) immigration office and the Bureau (B/C, bureau correspondence) dated January 26, 1942.

MARKINGS ON THE MANIFEST’S OCCUPATION COLUMNREFERENCES TO OTHER PAGES OR LISTS

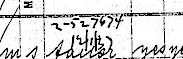

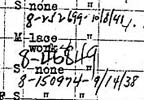

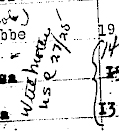

The most obvious markings in the occupation column relate directly to an occupation, and either correct or clarify the immigrant's trade. But the most perplexing annotations in that column have nothing to do with any occupation. Rather, they are number, letter, and date codes relating to later naturalization activity. They can be recognized by their being written--or the annotation beginning--in the occupation column, and by their adherence to a common format or style.

Numbers, Dates, Cryptic letters & Words

|

| #1 |

In 1926, the occupation column was set aside for annotations relating to the verification of immigration records for naturalization purposes. Since 1906, no immigrant who arrived after June 29, 1906, could naturalize until the government located their immigration record. Thus since 1906, after an immigrant filed a Declaration of Intention or a Petition for Naturalization in a naturalization court, the Bureau of Naturalization was called upon to provide a certification of the immigrant's arrival record. The certification, called a "Certificate of Arrival," was sent to the courthouse to satisfy the naturalization requirement that everyone who arrived since June 29, 1906 had to have a legal immigration record if they wanted to become a U.S. citizen.

|

| #2 |

|

| #3 |

|

| #4 |

All the verification for naturalization annotations follow a prescribed format containing one or more of the following elements: District number where the application was filed, application number, date of verification, and document issued. The table below identifies each element for the examples illustrating this page. Note that not all annotations of this type will contain every element. Examples 2, 4, and 5 do not indicate what document was issued, and examples 3 and 5 contain no date.

|

| #5 |

At times, Verification Clerks could not be sure the record found really did relate to the person who claimed that arrival record on their naturalization application. If there were enough significant differences, the clerk could not certify the arrival record. Minor differences were routine--ages one or two years off, height off by a few inches, or Americanized names (Jacob for Yankel, for example). But many years difference in age/date of birth, differing eye color, or place of birth, prohibited certification without further explanation. In those cases, the clerk issued a record (Form 505, or 404), but issued no Certificate of Arrival. Hence the frequent annotation "No C/A."

|

| #6 |

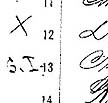

As noted above, there was no Certificate of Arrival requirement for immigrants who arrived prior to June 30, 1906. Nevertheless, one will see occational naturalization verification activity associated with pre-1906 lists. The example below is from a 1903 passenger list, and displays two characteristics of verifications for pre-1906 arrivals. One is the "X" between the district number and the application number. The "X" means the applicant did not have to pay the Certificate of Arrival fee, and in this case was exempt because he arrived before 1906. The other is the reference to issuance of a "C.L ." (or C/L), which is a Certificate of Landing. A Certificate of Landing served the same purpose as a Certificate of Arrival in the naturalization process, but since the latter were only issued to those who arrived after 1906, they needed another name for certifications from pre-1906 records.

Interpreting the Verification for Naturalization Annotations

This step is not so simple as it may seem. The presence of a verification annotation in the occupation column indicates the immigrant initiated naturalization activity between 1926 and 1942/43. In cases where no date is shown, there is no way to determine when this activity occurred. The application number is useless in finding naturalization records. Only the District key number is of limited help, in that one can usually use the number to determine a general location where the immigrant was living when he/she filed their application.

Unfortunately, the Naturalization Service would occasionally re-number all the districts. This means that Chicago might be in District #6 in 1927, but in District #11 in 1931. Chicago did not become District #9 until the early 1940's. Thus it is extremely important to know the date of the annotation if one is to convert the District number into a geographic region of the country.

The tables below show the Districts by number during different time periods. If you don't have a date, or if your date may fall on either side of a dividing line, check both or all tables for the locations. Some knowledge of the immigrant's history should allow you to guess which table fits your annotation.

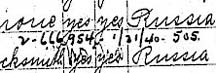

ANNOTATIONS REGARDING NATIONALITY & CITIZENSHIP

Annotated references to a passenger's nationality are usually, and usually should be, in the nationality column. In fact these references might be found anywhere on the list page, and are frequently found in the name column or the left margin (as were two of the examples on this page).

References to a passengers citizenship, either by birth or naturalization, were added upon arrival by the Immigrant Inspector. The fact of the person's citizenship is the Inspector's explanation of why the individual could be admitted without further questioning.

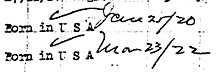

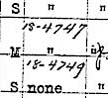

USB or US Born

Persons born in the United States are US citizens (unless they later expatriated themselves), and are entitled to admission to their own country. Thus the annotation "US Born" has great meaning to the passenger's admission under immigration law, and it is not surprising the fact of their citizenship would be noted. The "USB" annotation is often seen in the case of children returning home after a visit abroad with their foreign-born parents. These children, though citizens, were frequently listed on a "List of Alien Passengers" so they might be listed with their parents. The fact of their US birth is noted to explain why the children were not inspected in the same manner as non-citizens.

The same principle explains the example at right, taken from the "Visa" columns of a late 1924 passenger list. Those columns normally contain information about when, where, and what sort of visa was issued to the immigant. U.S. citizens did not need such documents, so their absence was explained by giving the birthdates of the children. These may have been taken from birth certificates carried by the parents as their children's travel papers. Some similar annotations have been seen to provide the specific birth certificate number.

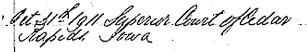

Though the example shown above right is from the name column, references to a passenger's naturalized status are usually found farther right, in the nationality column or in the blank space left in the columns under heading concerning health condition, height, weight, and eye color. This example indicates the passenger was issued naturalization certificate #383553. The number "2271" means the naturalization occurred in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn. The date may be the

date of naturalization, but could be the date of a verification. The six-digit number at left remains a mystery, and may have been added years later.

The images above come from the passenger list record of a naturalized citizen returning home. The annotated "USC" appears in the nationality column. Farther right, in empty space, is the reference to his naturalization in the Superior Court at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on October 31, 1911. In the case of both examples shown, the immigrant carried evidence of his naturalization (probably his naturalization certificate) on his journey, and the Immigrant Inspector took the information directly from that document. Unfortunately, on a busy day, the Inspector might note the "USC" status and fail to record the details of the passenger's naturalization.

The images above come from the passenger list record of a naturalized citizen returning home. The annotated "USC" appears in the nationality column. Farther right, in empty space, is the reference to his naturalization in the Superior Court at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on October 31, 1911. In the case of both examples shown, the immigrant carried evidence of his naturalization (probably his naturalization certificate) on his journey, and the Immigrant Inspector took the information directly from that document. Unfortunately, on a busy day, the Inspector might note the "USC" status and fail to record the details of the passenger's naturalization.

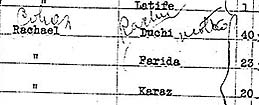

Occasionally one will find annotations that refer to other passenger lists. The other list may be another page of the same ship's list, or it may refer to a different ship arrival, on a different date, or at another port. The cross-references link passengers who are related somehow but not listed together, or links the various records of one passenger who arrived more than once. Cross-references are usually, but not always, found in the Name column.

References to Other Pages Of the Same Ship's List

References to Other Pages Of the Same Ship's List

The annotation at right indicates that two teenage steerage passengers are actually traveling with their mother. But their mother is a U.S. citizen, so she is listed on another page listing U.S. citizens. They are "with mother" on list of "USC"itizens, either page 27, line 25, or on lines 25 through 27.

The annotation at right indicates that two teenage steerage passengers are actually traveling with their mother. But their mother is a U.S. citizen, so she is listed on another page listing U.S. citizens. They are "with mother" on list of "USC"itizens, either page 27, line 25, or on lines 25 through 27.Movements between Steerage, First and Second Class Cabin

Some immigrants changed their class of ticket either just before departure or once underway, much like airline passengers today might "upgrade" to first class just before the flight departs. If the change came at the last minute or once the ship sailed, it was too late to be recorded in the final draft of the passenger list. As a result, pursers annotated lists to show the change. The example at right, found in the name column, indicates the passenger "transferred to Third Class." The example below explains that the passenger's Steerage list record is lined out because he transferred to Second Class.

Often, when a passenger moved between classes in this manner, the result is two records of the same person on the same ship--one record on the list as originally booked, and another on the list of the class in which the immigrant arrived. The same could happen when an immigrant for some reason "missed the boat" upon which he was booked and took the next ship instead. In those cases, he may appear to arrive twice, on ships arriving one after each other. If last minute changes could cause one immigrant to be listed twice, it is reasonable to assume the same situation might also cause an immigrant to fall through the cracks and not be listed at all.

References to Other Ship Lists

Many immigrants arrived in the United States several times, and consequently have more than one passenger list record. Sometimes these additional records are only suggested by Verification of Landing annotations found in the Left Margin. But at other times, the linkage between two records of the same person are unmistakable. One of the most striking differences between an immigrant's original arrival and a later entry is the "Americanization" of their names between arrivals.

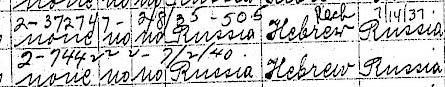

The examples below relate to three men listed together on the SS Pocahontas, which arrived in New York in mid-June, 1920. All three of the men were returning on that voyage, each having been previously admitted in earlier years. And all three have their records linked by references to earlier passenger lists. It appears all three had their records cross-referenced as a result of naturalization activity.

Note that since these annotations were made years before microfilming of the records, they make no mention of National Archives or LDS microfilm roll numbers. Rather, they rely on the volume, page, and line numbers. The page numbers correspond to "stamped" page numbers on the passenger lists that run consecutively through a volume (as opposed to other numbers original to the ship list).

MARKINGS IN OTHER MANIFEST COLUMN

In the Head Tax Column

Until 1952, there was a "Head Tax" on each immigrant entering the United States. For most immigrants, the tax was included in the price of their steamship ticket and paid by the steamship company. The same was true for passengers who came by railroad or ferry across the Northern and Southern Borders. Those immigrants who came "under their own steam" had to pay at the door.

Until 1952, there was a "Head Tax" on each immigrant entering the United States. For most immigrants, the tax was included in the price of their steamship ticket and paid by the steamship company. The same was true for passengers who came by railroad or ferry across the Northern and Southern Borders. Those immigrants who came "under their own steam" had to pay at the door. Many returning residents disputed their need to pay the Head Tax, claiming they already paid it upon their first arrival. They usually paid the tax, got a receipt, went to their home in the U.S., then pursued their refund by mail.

In the Can Read and Write Column

The Immigration Act of 1917 first required that immigrants coming to live in the U.S. permanently be able to read and write in their native language. Thus passenger lists after 1917 include a column asking whether the passenger can read and/or write, and in what language. Whenever an Immigrant Inspector suspected that an applicant for permanent admission was illiterate, he could send them for a literacy (reading) test.

The Immigration Act of 1917 first required that immigrants coming to live in the U.S. permanently be able to read and write in their native language. Thus passenger lists after 1917 include a column asking whether the passenger can read and/or write, and in what language. Whenever an Immigrant Inspector suspected that an applicant for permanent admission was illiterate, he could send them for a literacy (reading) test. The government initially tested the immigrants by having them read selected passages from the Bible, but it became clear this system could be controversial. So the Immigration Service soon developed a rather complicated system to perform the testing. First, each known language was issued a number. Then, a number of phrases and passages in each language were printed on slips of paper (one phrase per slip), and each phrase received a serial number. So each slip had one number for the language, and another for the phrase (i.e., #-####).

A second set of slips were printed in English, and numbered with the exact correponding numbers. The phrases usually contained simple instructions, such as "Get up, open the door, and return to your chair," or "Shake the hand of the person next to you." The literacy test involved first determining what language the immigrant spoke/read, locating a slip for that language, and giving the immigrant the test language slip and the testing official the corresponding English language slip. By reading the corresponding instructions in English and observing the immigrant's actions, even an Inspector who spoke only English could discern whether the person before him could read.

The passenger manifest would later be annotated with the number of the test slip. The notes indicated both that the immigrant was tested and exactly which test was given. A test slip number by itself usually indicates the immigrant passed. If he/she failed, the annotation often also includes the words "cannot read." If their illiteracy became grounds for exclusion (i.e., the reason to send them back), it should appear on a List of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry.

Hospital Stamps or Medical Annotations

Some records of immigrants who were held for real or suspected ailments bear a stamp reading "IN HOSPITAL." Many also have stamps indicating the end of their hospital stay, as either "discharged," "died in hospital," or "deported." If an immigrant was hospitalized, beginning in 1903 at New York the immigrant should also appear on a List of Aliens Detained or a List of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry. If they were hospitalized at Philadelphia ca. 1882 to ca. 1902, there may be additional records at the National Archives in Philadelphia. There are no known additional records for other ports.

Any immigrant whom the Public Health Service doctors thought might be sick, mentally ill, or otherwise unable to take care of themselves might be issued a Medical Certificate (click here to see a 1906 Medical Certificate). Those immigrants certified then went for a full examination by medical staff. They may not have been hospitalized, but many ship lists bear annotations noting Medical certificates, like those illustrated below, both certifying "senility":

Non-Immigrant Stamps

The question of how much money an immigrant had in his possession is related to his or her ability to support themselves in the United States and not become a Likely Public Charge (LPC). They needed enough money to pay for transportation, food, and lodging until they found a job, a place to live, etc. The amount needed would differ for different immigrants. Those coming to live with family members needed less cash on hand than those with only temporary lodging arranged. And those with scarce or marketable skills needed less money than common laborers, especially at times of high unemployment in the United States.

Immigrants were frequently less than truthful about the amont of money in their possession. Some claimed to have more money than they had, thinking the higher number would improve their chance of admission to the United States. Others claimed far less than was true, fearing their life's savings would be stolen by other passengers, or taken from them by corrupt border guards encountered on their journey.

Immigrant Inspectors often corrected the amount during immigrant inspection. Small variations are expected, explained by the fact that some funds might be spent while aboard the ship. Large differences are usually explained by the fact that many immigrants hid the fact that they carried large amounts of money until they arrived in America.

Discharged at Pier, Discharged at Dock

Some passenger lists contain stamps or annotations indicating a passenger was "discharged" at the pier or dock. First and second class passengers were generally inspected on board the ship and allowed to proceed while steerage immigrants lined up to board barges or ferries to Ellis Island. United States citizens listed on alien pages often display a "US Citizen discharged at pier" stamp. The example at right is from the record of a 26 year-old student "d[is]c[harge]d at dock" by Inspector Biglin. Whenever a passenger is so annotated, it means they did not proceed with others on that page toward extended immigrant inspection.

GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS

Many acronyms and abbreviations are found on the manifests and are used on this website. Below is a listing of the most commonly used acronyms and abbreviations, what they stand for and what page of this site further information can be found on.

Acronym/Abbreviation ... Stands for ... Found here...

404 ... Form 404 - Arrival Information ... Occupation Column

505 ... Form 505 - Arrival Information ... Occupation Column

ACL ... Alien Contract Labor ... Special Inquiry

B/C ... Bureau Correspondence ... Name Column

B-i-l ... Brother-in-law ... Record of Detained Aliens

B.S.I. ... Board of Special Inquiry ... Left Margin

C ... Certificate (usually) ... Nationality and Citizenship

C/A ... Certificate of Arrival ... Occupation Column

C.L. ... Certificate of Landing ... Occupation Column

CL ... Contract Labor ... Special Inquiry

D ... Detained ... Left Margin

Dcd. ... Discharged ... Other

Dep.-Excl. ... Deportable and Excludable ... Special Inquiry

D.O.S. ... Department of State ... Name Column

Husb ... Husband ... Record of Detained Aliens

LPC ... Likely Public Charge ... Special Inquiry or Other

Med Cert ... Medical Certificate ... Special Inquiry or Other

Nat or Natz ... Naturalized ... Nationality and Citizenship

N.O.B. ... Not On Board ... Left Margin

P ... Permit ... Name Column

Rech ... Recheck ... Occupation Column

R.R. ... Railroad ... Record of Detained Aliens

S.I. ... Special Inquiry ... Left Margin

Tel $ ... Telegram sent for money ... Record of Detained Aliens

USB ... US Born ... Nationality and Citizenship

USC ... United States Citizen ... References to Other Pages or Lists

V/L ... Verification of Landing ... Name Column

X ... "Detained" ... Left Margin

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)